Transgender history. Roots of a revolution

.

Dialogue of Katya Parente with Susan Stryker

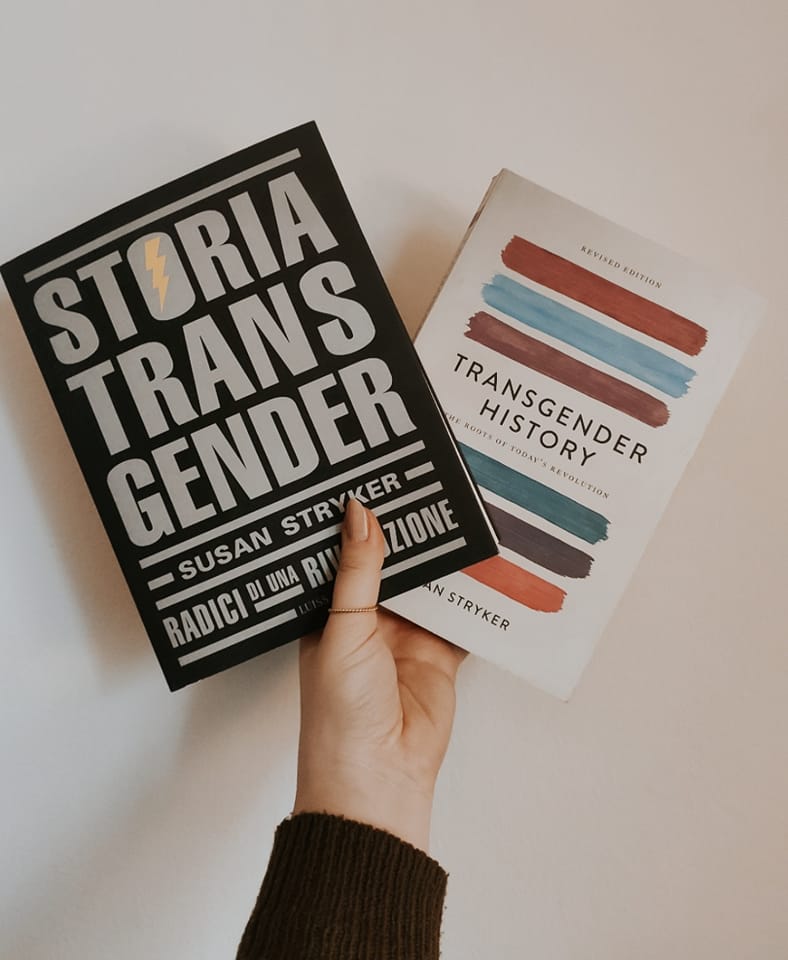

A very interesting essay by Susan Stryker, professor emerita at the University of Arizona and author of the documentary “Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria” has just released: “Storia Transgender. Radici di una rivoluzione” (Italian edition of “Transgender history. Roots of a revolution“). On the occasion of this issue we contacted the author, who was very kind and granted us this interview.

Tell us something about you…

I’m a 61 year old trans woman who transitioned more than 30 years ago. I grew up in a military family, lived on US Army bases around the world, but mostly in Oklahoma. I earned a Ph.D. in US History at University of California-Berkeley in 1992.

As an out trans lesbian I had a hard time finding work for quite a while due to discrimination, but managed to cobble together various ways of making a living from my research, activism, and creative practice. Eventually it all came together in a career I feel very satisfied with.

I worked for several years as the director of the LGBTQ archives in San Franciso, and became a documentary filmmaker. I was ultimately able to become a tenured professor of gender studies, and have helped establish transgender studies as a recognized field of study, including co-founding the interdisciplinary peer-reviewed journal TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly.

I retired from fulltime employment in 2019, and am now working on a variety of book and film projects. I live in San Francisco with my partner of 20+ years, and between us we have four adult children from various previous relationships.

The italian edition of “Transgender History” is out right now. Can you tell us about it’s structure?

The book was originally intended for classroom use, as part of the Seal Press’s Feminist Studies book series. Although the title is Transgender History, it should really be called Transgender History in the US since WWII, but the publisher wanted to claim more turf with a broader and shorter title.

Still, I think the book is useful in other national contexts, given that, to a significant degree, how trans issues emerged and developed in the US have a global impact.

If nothing else, the book provides an opportunity to compare and contrast different national histories. I’ve had many conversations over the years with Italian academics Vick Virtu and Stefania Voli, and members of MIT in Bologna, about the similarities and differences between Italian and US trans history.

The book has previously been translated into Korean and Spanish, and I know from looking at my social media and Academia.edu page that it my book is part of the conversations there about trans issues.

Transgender History begins with a personal introduction, followed by a first chapter on contexts, concepts, and terms. A second chapter surveys trans history from the mid-19th through the mid-twentieth century.

The third chapter focuses on the radical trans liberation movement of the 1960s, followed by a chapter on the backlash of the 1970s and 80s when a transphobic feminist discourse emerged along with increased pathologization and social control of trans lives.

The next chapter explores the second wave of trans activism in the 1990s through the early 21st century, and a final chapter is devoted to the so-called “transgender tipping point” in the 2010s, up to the point where another profound backlash set in.

In USA the book first appeared in 2008. What has changed since then?

The first edition is seriously out of date, written at a time when I think we were still in in the midst of the wave of activism that started in the 1990s, which had yet to run its course, and the future looked bright for further progress. Terms and concepts have changed quite a bit since then, and the future has become much darker.

The revised and expanded second edition of 2017 that’s been translated into Italian brought the terms and concepts up to date to that time; it asp takes the history up through the election of Donald Trump, and the deep political reaction that has set in around that time, where trans issues were just starting to become increasingly weaponized in the culture wars.

I think the book can provide valuable background information about how we have come to the current state of affairs, but obviously there needs to be a third edition that addresses the profound changes of the last 7 years–particularly the ways in which an anti-gender ideology that scapegoats and targets trans people has become such a prominent part of far right and populist rhetoric, discourse, and social movements globally.

How important is the minority perspective to change the reality that surrounds us?

I think it’s very important. And it’s interesting that you bring up the question of “reality.” So often, trans people are accused of being out of touch with reality–that we believe something impossible can be true, that “a man can be a woman or a woman can be a man.”

But there are a couple of things at stake in that claim that trans lives and experiences push back against. One is that trans people clearly demonstrate that it’s possible for one kind of biological body to develop more than one kind of gender identity or sense of self. I think of it as being like being left-handed: most human bodies have bilateral symmetry, and most people are right handed.

But some people live in a symetrical body and have a different orientation to it, living it in a way that is different from most other people, but still perfectly viable–and then of course, just as not all bodies have bilateral symmetry and are still livable, not all trans people are binary. I see all of this as simply part of human diversity, a less common way of being that is also perfectly routine and ordinary.

But the reality question goes deeper than that, and gets at what social scientists call the “social construction of reality.” Of course there are many things about “reality” that are not socially constructed–gravity doesn’t care what I think about it.

But how a given society understands the meaning of biological differences in reproductive capacity, how it uses (or doesn’t use) biology to assign people to personhood categories, how it relates these assignment practices to scientific or metaphysical worldviews or cosmologies, and how it then uses these beliefs about reality to administer and bureacratize all of our lives and to govern populations and territories is absolutely, totally 100% “socially constructed.”

So much of the violence and contempt directed at trans people is rooted in this “ontological warfare.” Some people whose social construction of reality considers people like me to be an impossibility are determined to say “this emperor has no clothes, I’m not going to accept that their perceptions and beliefs have any basis in realtity, and I won’t let them impose their false reality on me.”

This makes trans issue the perfect terrain for waging the contemporary culture wars, where we are witnessing a much broader struggle over which facts are facts and which are “alternative facts,” what’s actually happened and what’s a conspiracy theory. In this “post-truth” context, the social construction of reality is very much up for grabs right now.

The more I study trans history, the more deeply convinced I am that the dimension of the dominant social construction of reality that says it’s impossible to “change sex” is rooted in ideologies necessary to sustain the euorcentric world order that emerged from global colonization post-1492.

It is deeply connected to racist beliefs and practices that have used biological difference to try to bind some bodies in a permanently enslaved or exploited class–beliefs that try to turn one’s own flesh an inescapable prisonhouse. “Biological determinism” in both race and sex classification is rooted in a carceral logic. To my way of thinking, this is not to deny biology, but to contest “biologism,” or ideological uses of a physically real thing.

What trans liberation movements have in common with anti-racist and feminist movements is the assertion that “biology is not destiny.” Rather, it is we the living, in community with others, who say what our actually existing bodies mean. This is ultimately a political and cultural question, related to the values we hold.

Political activism or cultural activism? Which one was born first

They are two sides of the same coin. I’m a big fan of Felix Guattari’s concept of “molecular revolution.” Profound, radical change is always bubbling along just beneath the surface, as we all experience small-scale changes in things we feel drawn to or divorced from, things we prefer and feel good about and things we would rather not experience or connect with. I think most of that happens in the cultural realm, and that works of art and imagination can have a tremendous influence in shaping those desires and aversions.

And sometimes all of those multitudes of micro-scale things align with each other and begin to move many people in the same direction at the same time. Politics is the art of tapping into those massed molecular movements, putting names and stories to them, and intentionally accelerating their tendencies.

What’s next?

A collection of my essays from the 1990s-2010s, called When Monsters Speak, edited by McKenzie Wark, will be published next year by Duke University Press. I have a few mass media projects in various stages of development, but those sorts of things are always “pie in the sky” until maybe suddenly they’re not.

I’m trying to finish an ambitious book, under contract to a major US trade publisher, that blends historical story-telling with autoethnography, literary prose, and cultural theory.

I’d love to do a third edition of Transgender History in the next couple of years. We live in such precarious times–ecologically, politically, economically–and I want to do the things that are within my abilities to help make the world as good a place as it can be.

Which we should all strive to do. We thank Susan Stryker for her availability, with the wish to be able to successfully complete her projects.

Original text > La storia Transgender. Le radici di una rivoluzione