“Crossing a River by Stepping on Stones”. Being an LGBTQ+ Catholic in China

Dialogue between Alessandro Previti and Eros Shaw, a young gay Chinese Catholic, carried out within the framework of the Cornerstone Project*

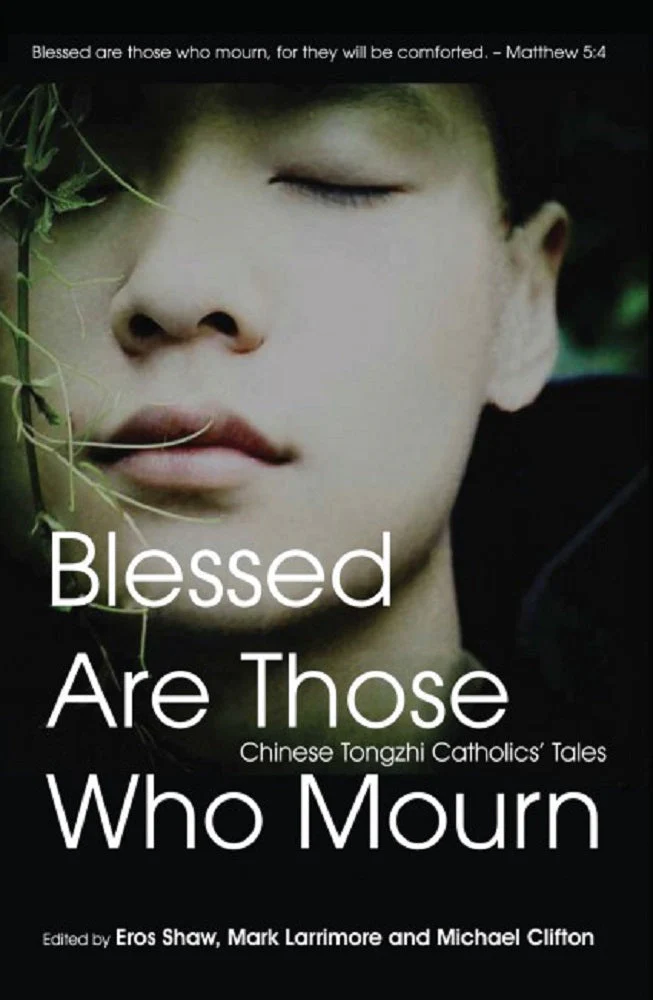

Eros Shaw is a young LGBTQ+ Catholic in China, where he obtained a master’s degree in theology. In the book Blessed Are Those Who Mourn: Chinese Tongzhi Catholics’ Tales (published by SIRD, 2022), he shares his journey as a gay Catholic in China, which began in 2009 when he “came into sporadic contact with other gay Catholics through the internet. There was no frequent interaction among us, and no one would have ever thought of creating an organization. Fear and geographical distances were major obstacles. That year, I moved to Beijing (China) for work,” where he met “a dozen LGBT Christians from various denominations.” This led to “the idea of meeting regularly to support each other. I was the only Catholic that day and remained so for a certain period of time.“

Today, Eros Shaw is actively involved in the China Rainbow Witness Fellowship, the China Catholic Rainbow Community, and the Global Network of Rainbow Catholics (GNRC). We asked him to help us understand what it means to be an LGBTQ+ Catholic in China.

In China, LGBT identity is often addressed differently than in the West, both culturally and politically. How does a Catholic LGBT person navigate this reality? What pressures come from family, society, and the Church?

I think there are a few cultural differences but more differences between the times. The pressure of marriage and childbirth that LGBT people in Europe and America faced in the past may not be needed now, but Chinese LGBT people still need to face it. Objectively speaking, from 2008 to 2018, Chinese society also shared the achievements of the LGBT movement in Europe and America. The LGBT Christians movement was also active, and our community was also established and developed at this stage. However, after 2018, the situation deteriorated sharply.

Faced with the decline in birth rate, society and families again target the LGBT group, and the Chinese church has too many issues to care about and currently cannot pay attention to LGBT issues. Therefore, Chinese Catholic LGBT people can only share some information and support each other with the help of the chat group.

Confucianism emphasizes social harmony and respect for family. Do you think this influences how LGBT people are perceived in the Chinese Catholic Church? Have you ever felt the duty to “not create disorder” for the sake of the community?

Absolutely. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states in 2357 that “homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered.” This is logically consistent. Not having children is intrinsically disordered, which creates disharmony in the family. The Chinese are born with the concept of a “harmonious” in their blood, so even though I do not have this idea of duty, I believe many LGBT people have.

Is it true that Christian churches in China often operate in a delicate balance between adhering to doctrine and adapting to the local context. Have you ever encountered priests or religious figures willing to discuss LGBT realities, even privately?

Localization is something that Chinese Catholicism has long insisted on. The most famous people, Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi, are often regarded as pioneers and are respected in the church and society. However, LGBT does not seem to belong to this kind of contextualized issue. However, paradoxically, some scholars believe that traditional Chinese society was not so harsh on homosexuality (just as some scholars believe that traditional Arab society was also the case). It was not until the introduction of Christianity that the homosexual community was treated harshly.

I met some clergy and nuns willing to accompany the LGBT community in private. They also shared their experiences in the book “Blessed Are Those Who Mourn —- Chinese Tongzhi Catholics’ Tales,” which I edited. On the contrary, I noticed that some clergy with homosexual identities avoid companionship and only pursue satisfying their personal desires (this should also be common).

Do officially recognized Catholic churches have space for dialogue on LGBT issues, or is the topic considered too sensitive? Have you ever heard of priests or religious figures in China speaking out in defense of LGBT people? Were there any consequences?

There is no space. But in recent years, with the different statements of Pope Francis on this issue, some Catholic WeChat public accounts in mainland China have indeed supported the LGBT issue, but they have been attacked.

I heard that the bishop of Hong Kong is interested in discussing this issue, and I also sent him my book through someone, but there has been no follow-up so far. I know it is very difficult.

Have you ever had experiences with underground or unofficial Christian communities? If so, are they more open or more rigid regarding LGBT inclusion?

Yes. But their focus is less likely to be on LGBT issues but on their own situations.

Many young people in China, even those who are not religious, are exposed to LGBT culture through social media and global influences. Is this new generation impacting churches? Is there a shift in religious discourse on gender identity and sexual orientation?

This is also a real phenomenon. I have seen young catechumens in different catechism classes challenging priests on the LGBT issue. The priests can hardly respond and only emphasize that this is the church’s position. But I think this kind of influence is happening, just like the universal church.

Are there parallels between the situation of LGBT people and that of religious minorities in China? How do LGBT believers deal with this double marginalization?

Yes, absolutely. LGBT Catholics face this double marginalization every day, and while their reactions may vary, they are undoubtedly under tremendous pressure. The dozens of stories I collected in “Blessed Are Those Who Mourn” are their real situations.

Many Chinese LGBT communities find refuge in cultural or digital spaces rather than religious institutions. Could the Church play a role in offering support without conflicting with the dominant culture?

The Initiators and leaders need to be there, and they need to be courageous and wise, but I don’t see that happening in the current situation.

If you could speak directly to the Pope or the leaders of the Chinese Catholic Church, what would you ask them?

I would say to the Pope that I am grateful for his kind words toward LGBT people over the years, and I understand his difficulties and pray for him. If possible, I want to invite him to read the book “Blessed Are Those Who Mourn”, which was also presented to him through GNRC on October 25, 2023.

To the leaders of the Chinese Catholic Church, I hope they can remember that they are shepherds and should be open to everyone.

Tell us your story? See “Blessed are those who mourn, pp.260-264.”

*The Cornerstone Project, coordinated by Jonathan’s Tent (Italy), which aims to collect and offer testimonies and reflections from many voices on the welcome of LGBT+ Christians and their families in our Christian communities (Catholic and Evangelical). What are the challenges, possibilities and ways in which it can be achieved? What problems does it pose and what possibilities does it open up? How theology and the study of the Bible can help us create cornerstones with which to build more inclusive Christian communities, so that “The stone that the builders rejected”become“corner head” (Luke 20:17-18)

The Cornerstone Project is also supported by: the Faith, Gender and Sexuality Commission of the Baptist, Methodist and Waldensian churchesand from Italian Evangelical Youth Federation (FGEI) and by some Christian realities from different parts of the world: Drachma Malta, Global Network of Rainbow Catholics, China Catholic Rainbow Community (China) e Rainbow Home of Seven Sisters – RHOSS (India). The 2025 edition of the Cornerstone project is co-financed by the fund Eight Per Thousand of the Waldensian Church (OPM/2024/47240)