Return to Beirut. The Lebanon told by an Arab Queer

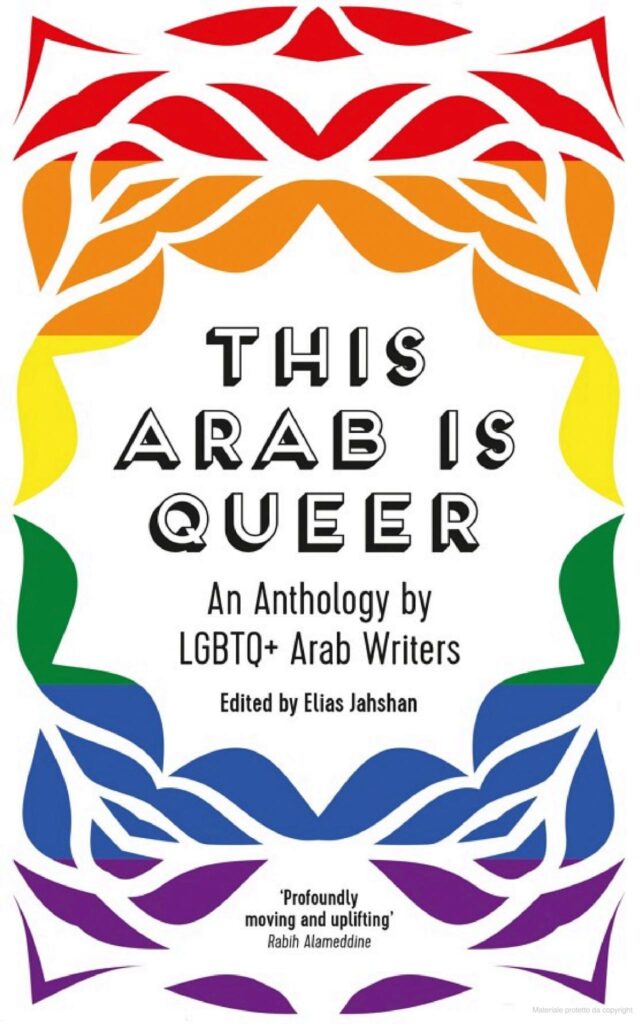

Text by Saleem Haddad* taken from the book This Arab is queer: an anthology by LGBTQ+ Arab Writers (This Arabic is Queer: an anthology of Arabic LGBTQ+ writers) **, edited by Elias Jahhan, publisher Saqi Books (Great Britain), 2022. Freely translated by the volunteers of the Gionata project.

My flight lands in Beirut just before dawn. To immigration, a young officer with a surgical mask under the chin stamps my passport and nods me to pass. My father awaits me in the hall of arrivals. The sun has not yet arisen and the city is wrapped in darkness. The roads are silent while we drive through the dark streets towards the family home in Achrafieh.

The street lamps don't work much these days and I don't remember the last time they did it. Eighteen months have passed since my last visit. While going through a tunnel, I point out to my father. "Yes. From the Thawra (revolution) ”, says my father with a sardonic smile, pronouncing the word Thawra in a feminized way to diminish the movement, using a mixture of misogyny and anti -revolutionary policy that knows that it will bother me.

During my last visit, we had passionately discussed the virtues of the revolution. I derided his cynicism and he raised his eyes to the sky for what he called my "western naivety".

It is true, at the time I was taken by the dream of a possible future, by the collective desire for something new, to free myself from the chains of corruption and fear that the lords of the war had instilled for generations. Although I am large enough to know, to remember, that such collective actions rarely translated into a better life, at the time my desperate desire to believe in the possibility of a better future had had the better of every logic and on every reasonableness.

My parents returned to Beirut in 2019. For my father, Palestinian-Liberation, it was a return home, a return that has long been expected. He had left Beirut during the civil war and his dream had always been to return to the city where he was born and raised, the one that had shaped his identity and his sense of himself. All his previous returns had been temporary, interrupted by political instability and more profitable offers in the Gulf. This, however, seemed to be the final return: after decades of distance and multiple movements, my father was returning to "home", or at least to the place closest to home for a Palestinian in exile.

I too, during my last visit, had thought of returning. I left the region in the summer of 2006, the summer in which Israel bombed Lebanon. Immediately after the end of the bombings, I flew to London. I thought I deserved more than I had available and more than what my surname could offer me (in a world where the surname was the key to unlock access and opportunities).

When I left, I told myself I wouldn't return without a European passport. I would not have returned until I took all the opportunities at my disposal, including the possibility of exploring my sexual desires to the maximum.

I thought my departure was not an escape. I told myself that my decision to leave was led by intellectual curiosity, by the desire for exploration and adventure, by ambition and perhaps also by the belief that I somehow reconnecting me to a sense of cosmopolitanism that belonged to my ancestors. I would be back, I said to myself, when it was the right time.

Yet, after fifteen years in Europe, I had started to feel an ambiguous solitude. This solitude was deeper than a community removal, families, ideologies or political parties. I would never have been really "here", I knew it, as far as I tried. Nor did I want to be particularly. But I wasn't even "there". More than a distance from the world, I felt foreign to my own body, to my sense of self: my identity, my sense of the place and even my desires.

Now, while I was returning to the car from the airport, my father mentioned the Thawra And he brought me back to that period in which my individual pain dissolved in the euphoric anger of the collective. If we had been eighteen months earlier, I could have discussed again with him and we could have passionately debated the revolt as we did then.

But July 2021 is a very different period from October 2019, and I let the paternal provocation run. “Yes, from Thawra”, I answer.

I had not planned to stay so long, but these are extreme times. The truth is that, even after all - the economic collapse, the pandemic and the explosion (of the port of Beirut) - something else has kept me far. I delayed an inevitable mourning. My journey to Beirut will force me to confront the death of Lebanon I knew once. He will also force me to cry my dream of returning.

I knew about the explosion of August 2020 while I was training in the gym in Lisbon, where I currently live. My mother sent a series of photographs of our destroyed house on Whatsapp. The windows were skipped. Each surface was covered with glass. The family paintings had exploded by the frames. Sketch of blood of my brother dotted the marble floor.

Among the images sent by my mother there was a video in which she walked for the house, showing the extent of the damage. It was silent in the video, in shock, and I could hear the sirens in the distance. His steps creak as he walked on the glass carpet.

I stayed in the center of the gym for a long time, examining the photos and sending messages to friends. Around me, the world continued as usual. A boy made my sweet eyes near the bench for squats and continued to look in my direction, unaware of the fact that my world had changed in a moment. The gym officer reproached me for not cleaning the weights after using them.

I thought if it was appropriate to leave the gym. I reasoned that there was nothing I could do so far. I went back to my training. It was only in the middle of my second series of exercises that suddenly understood the real scope of the explosion.

Maybe I left the shock in which I was, or the protective enclave in which I had spent the last fifteen years to protect myself from an endless tragedy collapsed on me. I left the gym and went home.

It was impossible to elaborate mourning from afar. In the distance, the world continues normally. Attention moved to holidays, meetings, to the most recent news. My world had exploded, but I lived in a universe that continued to travel.

When it emerged that the cause of the explosion had been negligence and corruption by the usual suspicions, my pain quickly turned into anger. It was not enough that the lords of the war had divided, robbed and depleted the population of my country. Now they had literally skipped my city in the air.

Those first weeks seemed to me to cross a ford in the mud. I tried it when I was in Beirut during the Thawra (the revolution) That feeling of being consumed from the present moment.

Now, instead of being consumed by collective hope and the possibility of change, I was drowning - alone and far - in my pain and anger. The explosion, which had destroyed part of the city of Beirut, had been the coup de grace for my already vague return plan.

Perhaps, realizing my sudden need for new roots - a few weeks after the explosion that had devastated my father's hometown, mutilated my friends and almost killed my family - I put a seed of avocado in half in the water, in a glass.

Over time, from the thin roots that sprung from the bottom of the seed, a small trunk emerged, which divided the seed into two. Every day I controlled the sapling, I took care of it, I changed the water, I monitored the growth, gently scratched the mold that grew on the roots with an old tooth toothbrush. The process became a form of meditation, clinging to hope - however small - in the absence of hope.

During the winter, while the pandemic worsened and Lisbon recorded tens of thousands of new cases a day, I started dedicating myself to gardening. I plant tomato and cucumber seeds, chillies and peppers of master, basil and mint. In homage to my Palestinian roots, I passed my aversion to clichés and bought an olive tree.

With the arrival of spring, I took care of the plants, sinked my fingers into the rich ground. It was a reminder to welcome the passage of time, to appreciate the fruits that time can bring. Because the passing time is not just loss, I repeated myself. Something earns, too.

In the summer of 2021 it was impossible to ignore the misery on the streets of Beirut. Infinite files for petrol, almost absent electricity, a number of homeless never seen before. Many of the cafes, restaurants and bars of my adolescence had exploded or had closed, and those who were still open were mostly empty. The garbage was everywhere - now the rule in Beirut for some time - but the dirt and the fier in the midsummer AFA were a separate hell.

From my house to Lisbon, I had observed the Lebanon to collapse, and with it my hopes to return. But following the news from afar is one thing. We are quickly addicted to words like hyperinflation, dollar reserves, political stall, gas deficiency. It is quite something else to experience the tangible signs of the collapse on one's skin, to feel their weight, see closely the tiredness and trauma in the eyes of loved ones.

It takes time to get used to the new rules: you must never pay with paper (the official exchange rate is much more favorable to the Lebanese lira than the real one of the black market), therefore you have to bring with it bacopes of cash. Walking at night on the dark roads with full currency pockets requires a certain adaptation, but more than everything, the collapse seemed engraved in the psyche of the inhabitants of the city.

People were more irritable than usual, quick to anger, apathetic and suspicious. My friends and family were traumatized. Many friends had left the country, and most of those left had abandoned the city (and traumatic memories linked to it) for a more peaceful life in the villages.

With my family we did the usual "family things". We spent a few days on the beach. We ate in our favorite mountain restaurants, we went to our usual place for the Knafeh Kanak (Arabic dessert with cheese) and we visited what remained of our favorite shops and restaurants. But the experience had a ghostly aura, like consuming a meal inside a corpse.

"Is it really so serious?" My mother asked me one day, after my comment on the strangeness of the situation. "Yes," my brother and I replied in unison. "You just lost the sense of perspective."

In the first days, my mother encouraged me to take a walk in the areas destroyed by the explosion at the port of the previous year. "It is important to see it with your eyes," he said, as if he was encouraging me to identify the body of a relative to accept his death. For the first week of my trip, resisted.

In the end, in the seventh or eighth day, after continuous insistence of my mother and also to escape the cutting of electricity in the late afternoon (ninety minutes that seemed a thousand, in the heat and in the most atrocious humidity of the day), I decided to walk through the destroyed neighborhoods that were once my usual meeting places in Beirut, a streets full of coffee, bookstores, bars and shops.

The explosion site seemed the physical proof of a much deeper collapse. I tried not to fix the destruction: I didn't want to feel a stranger. But now I was a foreigner, I realized it. Everything seemed to me foreign.

I looked at a balcony. An elderly woman with a cigarette in the mouth, short hair dyed of blonde and a blue dressingaglia, was taking care of the red roses on her terrace, and I thought of my small garden at home. The glass windows of his house were brand new, a strident contrast with the old building whose columns were strips of dirt.

Further on, along Mar Mikhaël, I notice a British humanitarian operator I know. He is guiding a group of foreigners in the rubble of my neighborhood. For a moment I think I stop to greet her, but then outcome. It is different for me. Here are memories, families, friends, reduced lives powder. For them it is an experience to tell, a fragment to be added to the conversations of their cocktail parties in Paris, Geneva, Brooklyn.

For me it is my life, or at least it was. The world I left behind me no longer exists. The friends I grew up with, with whom I played in the courtyards of the school and drinking in the bars at the beginning of my twenty years, are scattered around the world as confetti. Those who remain, including my family, bring deep scars on me.

Reconstructing does not only mean returning, it means having to redo everything from the end. I should bring back all those who have left with me, erase the anxiety wrinkles engraved on the faces of those who have remained. But it is impossible. You cannot put the confetti back into the box.

I am writing to a lover who still lives in Beirut. He replies after five minutes, invites me to his house. It's Friday evening, I spent the afternoon between sonnellini and hashish, and as I walk ten minutes in the darkness towards his apartment I still feel intoned. At the door we embrace long.

Eighteen months had passed since the last time we saw each other. An attempt to have online sex, a few days after the explosion - he still had points - had not been up to our real meetings. Now, in person, let's not waste time: we immediately head to the bedroom and, as always, it is he who takes control. It undresses me, kisses my chest, then he bites my nipples until I cry out for pain and I shoot back. He smiles and whispers: "Everything is fine, come here", and attracts me again with other kisses.

[...] Later he leaves my hands free and lie on the bed. I kiss him on the neck, on the chest, then I go down the stomach to the thighs. I look at it. "You can love me," he says, as if he granted me a privilege. "Do you really want it?" I ask him. "You want it," he replies, and he is right.

It is incredibly beautiful: warm eyes, long hair up to the shoulders, a perfect body, large, muscular, with just a little more meat to testify that it lives well. I look at him, in this dark room, in a dull city, and I wonder if his body seem so perfect because it is his, because it is part of him, of his shy smile, of the way he is unbridled in bed but reserved outside, of his precarious balance between desire and distance, of his ability to attract me without ever letting me approach too much.

[...] I remember why I spent eighteen months to desire it, because I wrote and published an entire story inspired by him. Something in his eyes, in his smile, in his calves reminds me of the house. He takes me back to childhood, to the Mediterranean beaches, to the hot and humid summers. It is almost as if we were brothers.

What I am really adoring, I wonder, while I pray the lips against the soft skin of its ankles, then along the soles of the feet and between the fingers. Is it his body that I want or something more elusive, something intangible that I unconsciously projected on his meat?

Yet, at this moment, despite everything that is foreign to me, I feel at home in my desire. It is a sort of return, a return to live the moment, who writes it, to give him light without shame. It is a return to myself.

Afterwards, while we lying side by side, he asks me: "How long have it been?"

"Almost two years", I reply.

He shakes his head: "It happened so much."

[...] We take a shower. I am stunned when a towel gives me. Talk, but I don't listen to it. I am still too shaken and my mind is trying to elaborate the fact that, after eighteen months, after a revolution, an economic collapse and a pandemic, I finally returned to Beirut. Or at least, to what remains of it.

[...] He asks me to stay for a drink. I would like, but I fear the roots that I could plant in this poisoned land, which seems sterile, unable to bear fruit. I don't know what you scare me more: the city or him.

The next morning, I leave Beirut. The day before (the Lebanese Prime Minister) Hariri resigned, again, unleashing protests and road blocks along the road to the airport.

It is the first time that I go back and I have not prolonged my stay. I go without regrets, as you leave a toxic lover to whom we cling too long in the hope that it could complete you. Now I know it was just an illusion.

At Istanbul airport, rent a room to sleep four hours. I fall asleep immediately. I dream that the avocado plant that I had grown after the explosion died. The dream is so vivid that I believe it real. Only when I return to my apartment, seeing that it grew by five another centimeters, do I understand that it was only a bad dream.

* Saleem Yacoub Saleem Haddad (in Arabic: سδيم حداد) was born in 1983 and is a writer, director and humanitarian operator of Iraqi-German and Palestinian-Liberation origin, whose debut novel Cheek It was published in 2016 (in Italy published with the title Last lap to the Guapa by Edizioni and/or April 21, 2016). Contributed in 2022 to the anthology This Arab is queer: an anthology by LGBTQ+ Arab Writers with the story "Return to Beirut"Which tells his return to Beirut and his decision to leave Lebanon forever.

** This Arab is queer: an anthology by LGBTQ+ Arab Writers It is a collection of essays and stories written by Arab authors LGBTQ+, edited by Elias Jahhan and published in Great British by Saqi Books in 2022

Through stories that range from autobiography to political and cultural reflection, the authors tell what it means to be queer in often hostile contexts, facing themes such as coming out, family, migration, religion and desire for belonging. The stories it collects are not limited to talking about oppression and difficulty, but also celebrate resilience, love and freedom of expression in all its forms.

With contributions from writers such as Saleem Haddad, Randa Jarrar and Zeyn Joukhadar, This Arab is queer challenges stereotypes and expands the representation of sexual and gender diversity within the Arab world. A fundamental reading for anyone who wants to understand the multiple facets of the queer identity in the Arab world of today.

Original text: Return to Beirut