The island of femminielli. Lives in fascist confinement

Article by Arianna Pescini published in Focus Storia n.86 of December 2013, pp.82-85

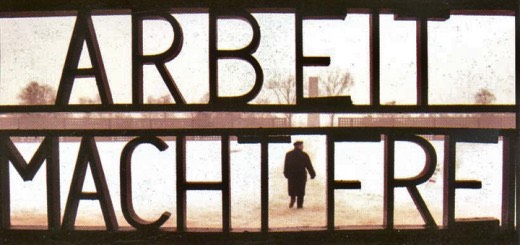

They called them like this: femminielli, arrusi, pederasts... With these ironic and contemptuous nicknames, fascist society showed its hostility towards gays. Going so far as to relegate them to plots of land as far away from civilization as possible. This is confirmed by the story of the dozens of homosexuals sent by Mussolini in the middle of the Adriatic, but also in Lampedusa and Ustica.

One of the many dark pages of the regime, which eliminated the crime of homosexuality from the Rocco penal code project since in the new fascist Italy it was not allowed to even imagine such a crime. And he kept the measure of confinement for preventive purposes, so that they would not "dirty" the image of the country: two pieces of gossip and a complaint were enough to receive a warning. Or, in the worst case scenario, end up banned for five years on remote islands. But who were they and how did the exiles live this parallel reality? Here we tell you the story of the border residents of the Tremiti islands.

THE SICILIAN CLAN

Between 1936 and around 1940, 300 gays were in fact condemned as "dangerous to public safety". There were those who remained in exile for three years, those for five, those who returned home earlier because they had important relatives. In 1939, around sixty prisoners ended up in San Domino, the largest of the Tremiti islands, on which the fascists built some concrete barracks to house the prisoners, without electricity or running water. There were students, workers, tailors, farmers. From the North and the South. And many very young people.

One of them wrote: “For eight months I have been longing for freedom every day, at all hours, at all moments. Life without it is dead, especially for a young man in his twenties. And what crime, what evil have I committed to be thus deprived of this great treasure? What scandal can I be blamed for?”. Of the approximately sixty gays who arrived in San Domino, forty-five came from Catania, all arrested and convicted at the beginning of 1939, during a "witch hunt" unleashed by the then police commissioner of the Sicilian city, Alfonso Molina. But why this fury?

«There is no specific directive of the time that explains this frantic investigation» says the historian Gianfranco Goretti, author with Tommaso Giartosio of the book The city and the island. Homosexuals in confinement in fascist Italy (Donzelli editore), “Apart from the diligence of the police commissioner, both the racial laws recently promulgated by Mussolini (1938) and the unsolved case of a murder committed in 1936 certainly played an important role, which indirectly involved some of those arrested. Molina thus found files on his desk with compromising, sometimes scandalous, stories which convinced him to act resolutely."

On the official document of the measure the words of the commissioner were clear and sharp: "The spread of degeneration in this city has drawn our attention" he wrote. “I consider it essential, in the interests of morality

and the health of the race, intervene energetically so that evil is attacked and cauterized in its foci. Police confinement helps this, in the silence of the law." Thus the "arrisi" of Catania found themselves in San Domino.

LIVES IN CONFINITION

The border prisoners were brought to the island in chains, but were then left free to move, although supervised by guards who arrived in turns from nearby San Nicola. Waking up at dawn, the "guests" made do with the 5 lire a day that the state gave them (not much, if you consider that at the time a kilo of bread cost 2 lire and forty); or managing to do the same job they did at home.

“The families sent us parcels, food, clothes” Giuseppe B., an inmate from Salerno, recounted in an interview from 1987. “But everyone tried to do their job, shoemaker, tailor, farmer, and so on.” The day ended at eight in the evening (at nine in the summer), when a bell warned the border workers that it was time to return to the dormitories, under the strict control of the fascist sentries.

The only contact with the outside world was the island of San Nicola, a quarter of an hour away by boat, where political exiles and the local population found themselves: "The neighbors of San Domino went there to do some shopping" says the writer Paolo Pedote, author of Poppy Island (Area 51 Publishing), «always followed by Fascio or uniformed guards. The locals did not treat them like criminals, but observed them with curious amusement. Everyone knew that there were "pederasts" on that island."

Many boys experienced their condition as exiles as a disgrace, a shame for their families. “Here, in this inertia that depresses me, what good can I do?” wrote a twenty-year-old to the Ministry of the Interior. “The more time passes, the more gloomy, sad and apathetic I become. […] I desire acquittal because I want to serve my country and erase the stain of dishonor from my family's forehead. And then return to the seminary to lead a retired life; it is the only way to repair the scandal.'

Other testimonies available in the State Archives are instead lighter, because on the island there were also those who tried to take the long period of "forced stay" with spirit: "We tried to live as well as we could. It served to pass the days. We laughed, we did theatre, we celebrated parties and we prepared welcome tables for the new arrivals. we could dress as women without anyone saying anything." Some love stories and interests were also born: “there were even stabbings between Sicilians there, out of passion” Giuseppe B would later recount. “Then we didn't have enough money; and some were forced to engage in hustlers with those who were richer."

In the evenings, fishermen often arrived to meet up with the "femminielli", and even quite a few fascists and carabinieri "wanted to satisfy the whim" of a clandestine sexual adventure.

THE FIRST COMMUNITY

For some, San Domino represented an opportunity to be themselves: «This island paradoxically became the first place where homosexuals lived without hiding» explains Pedote. «And without the fear of having to escape due to one's nature».

When in June 1940 the structure was converted into an internment camp for foreigners, due to Italy's entry into the war, the homosexuals returned to their cities, with the sole obligation of signing in at the police station every evening.

And the former prisoner Giuseppe B. tenderly remembers the moment of departure: “After all, it was better there than here, in my time if you were 'feminine' you couldn't even leave the house, you couldn't make yourself noticed, otherwise they would arrest you. When we left the Tremiti there were those who cried, those who didn't want to leave the island." Returning meant starting to fight for one's rights again.

HOMOPHOBIA IN BLACK SHIRT

- The crime of homosexuality it was not present in Italian legislation even before fascism. In 1927, when the famous Rocco penal code was being born, an article was foreseen that was supposed to legislate on the issue, 528: it punished anyone who had homosexual relations with prison from one to three years. In the end, however, the text was not included in the code and it was preferred to use police confinement which avoided going through trials, lawyers and the judiciary.

- Prevention. This modern form of exile in the homeland consisted of a "crime prevention" measure: it allowed the authorities to arrest and submit to the judgment of a special provincial commission anyone who was even just suspected of pederasty based on rumors or spying from neighbors. . •For homosexuals, the already difficult permanence in a traditionalist society which had made machismo its basic philosophy and the traditional family the cornerstone of fascist society was thus aggravated.

- The penalties. Depending on the severity or the evidence collected, the arrested person could receive a warning, a warning (a kind of house arrest) or confinement for up to 5 years. After the racial laws introduced in 1938, the situation worsened further: gay prisoners became "political prisoners", since homosexuality also became synonymous with anti-fascism, or an attack "on the dignity of the race" and on the values of fascist ideology.

- Read more: Paolo Pedote, Poppy Island. The first gay community in the world that invented the Duce (without knowing it), Area51 Publishing, 2013, Ebook; Gianfranco Goretti, Tommaso Giartosio, The city and the island: homosexuals in confinement in fascist Italy, and. Donizelli, 2006, 275 pages